Latin American and Caribbean Faculty of Social Sciences – Program Uruguay

FLACSO Uruguay

FLACSO Uruguay is an international academic program based in Montevideo, focused on research, postgraduate education and technical cooperation in the Social Sciences.

History

The Latin American Faculty of Social Sciences (FLACSO) created in 1957 is an international, intergovernmental, regional and academic and plural organization, made up of 18 Member States and two extra-regional observers, to promote teaching and research in the field of Social Sciences. FLACSO carries out academic activities in 13 countries in Latin America and the Caribbean.

More information about the FLACSO system: https://flacso.org/index.php/en/sistema

The government in Uruguay ratified the adhesion of the Republic of Uruguay to the FLACSO Agreement in 2006, thus establishing the FLACSO Uruguay Project. FLACSO Uruguay is recognized as an international organization operating in Uruguay.

In May 2014, FLACSO’s regional bodies approved the upgrading of FLACSO Uruguay to the category of “Program”. This new status enables the headquarters to offer the Masters degree level.

FLACSO Uruguay carries out academic diplomacy with the aim of fostering ties of knowledge and friendship between peoples and cultures.

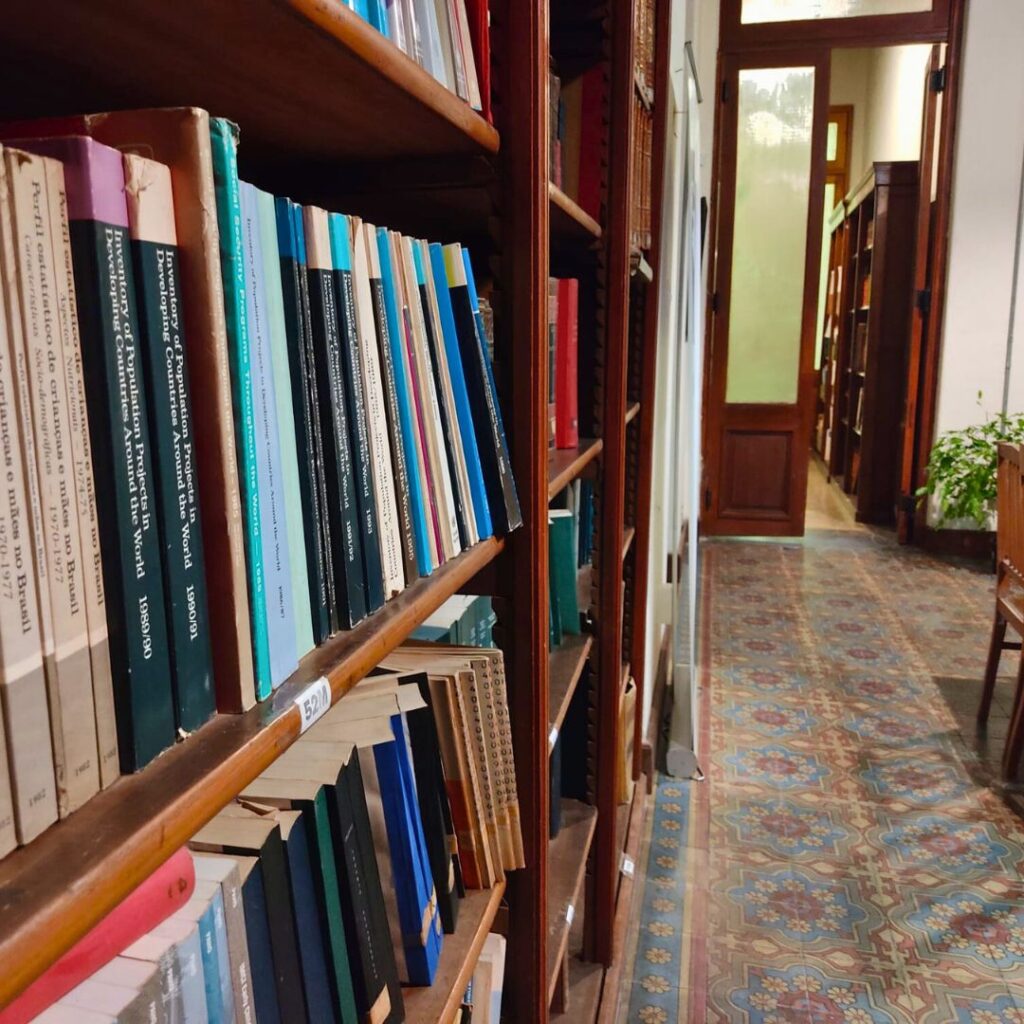

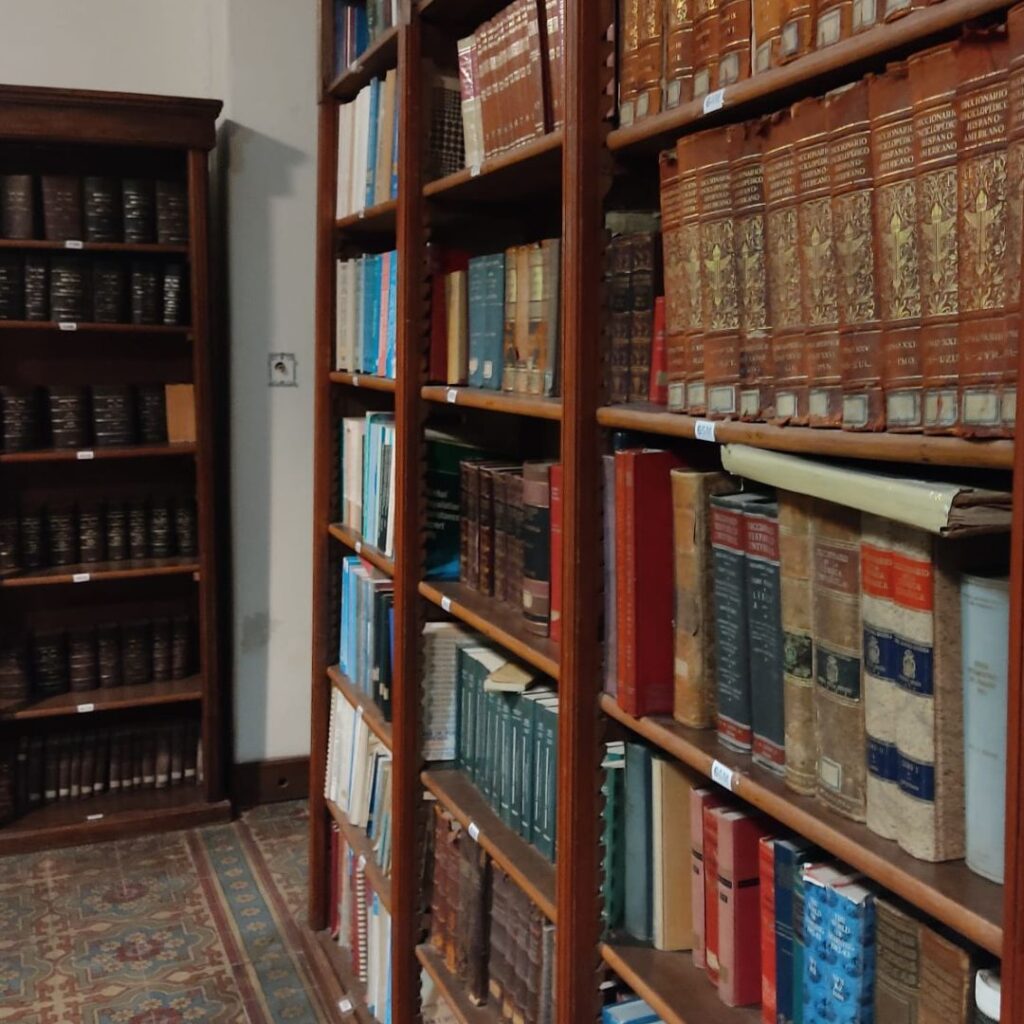

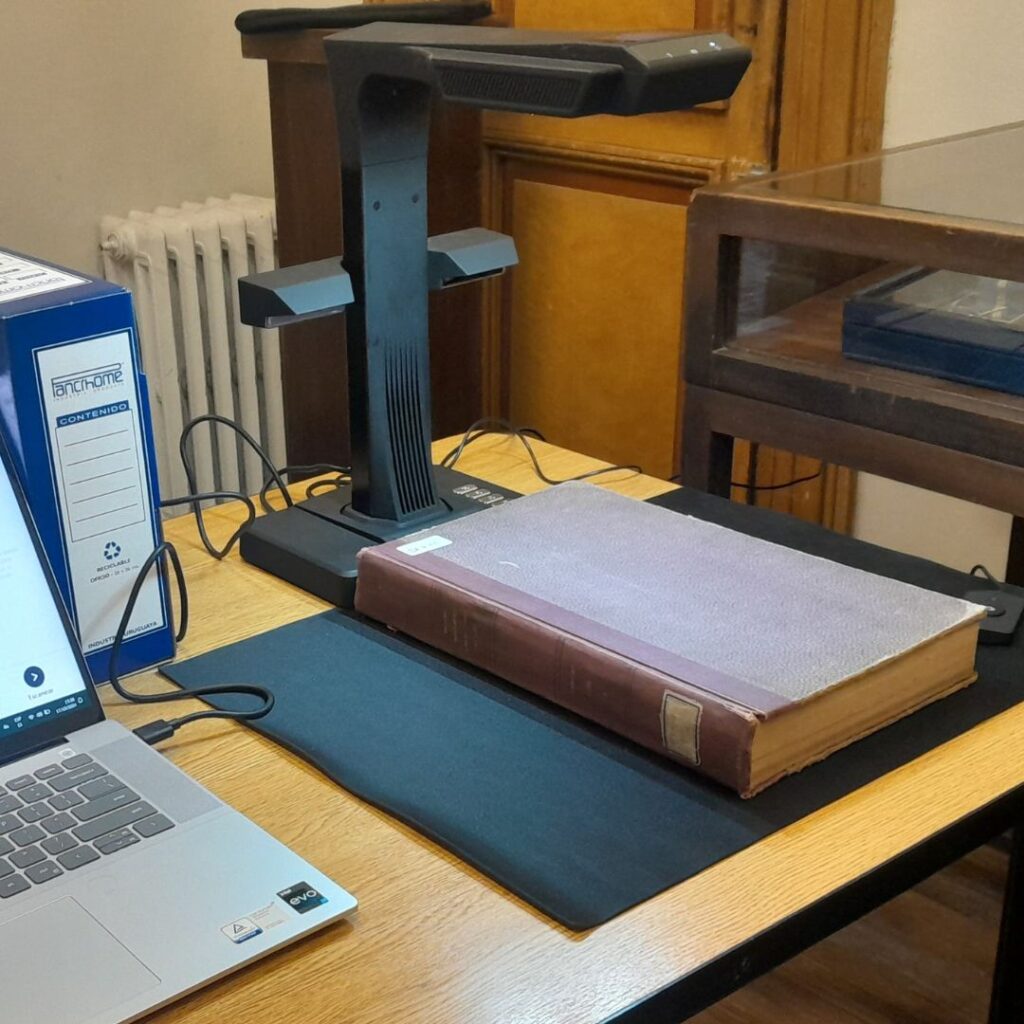

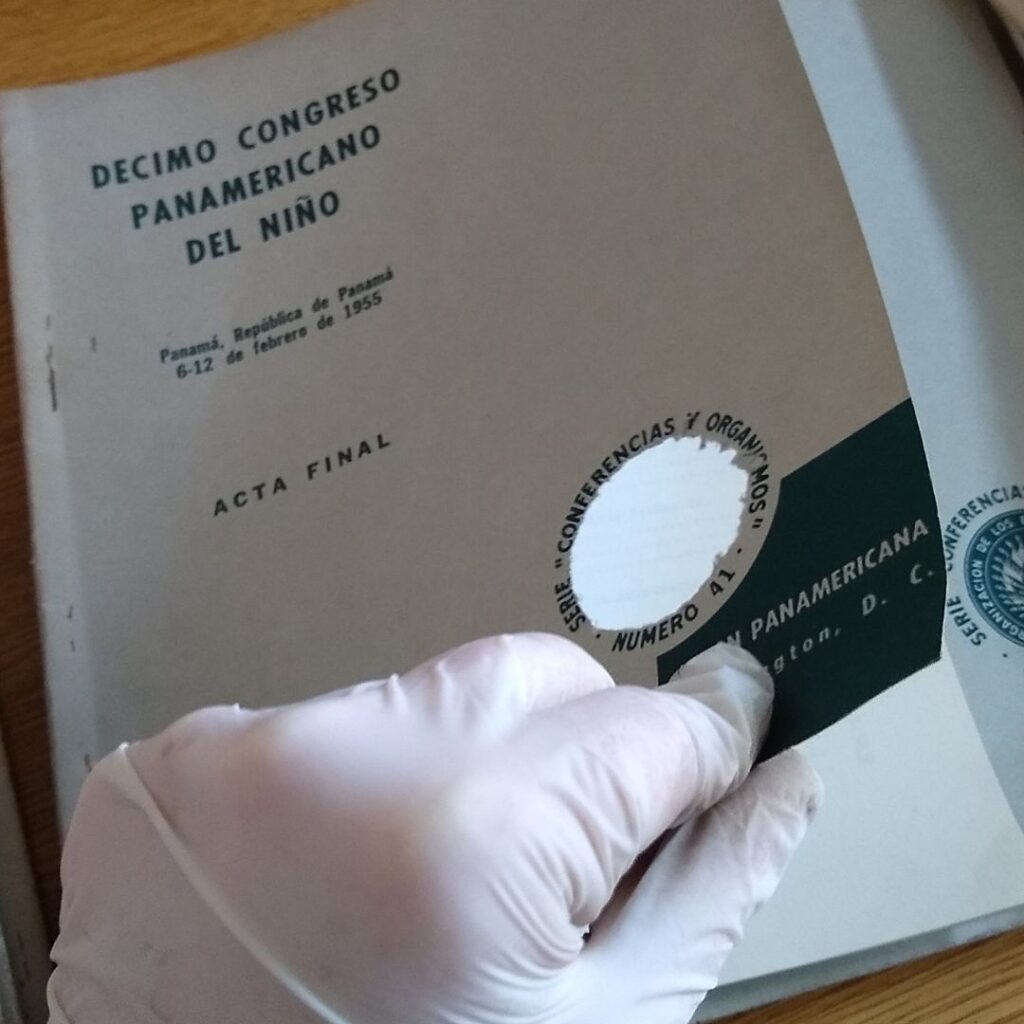

Luis Morquio Archive and Library

The Luis Morquio Archive and Library, which belongs to the Inter-American Children's Institute, was created in 1927. It was initiated by the Uruguayan paediatrician Luis Morquio as part of the establishment of the Inter-American Children's Institute. Its current headquarters are located in Montevideo, at 2884 8 de Octubre Street.

The Inter-American Children's Institute Archive is one of the longest-standing institutions within the Inter-American system. It was established with the objective of maintaining and preserving the documentation recorded by each Member State. The documentation comprises a wealth of works by individuals involved in actions and knowledge related to children and adolescents across the American continent.

The Luis Morquio Library and Documentation Collection represents a significant cultural and documentary heritage for the peoples of the Americas, providing a unique record of key historical events affecting children and adolescents on our continent. Its collection is of relevance for research with medical, legal, historical, pedagogical, and sociological perspectives. The library contains over 20,000 volumes, in addition to thousands of uncatalogued documents.

Since 2012, the archive has been in a state of neglect. The archivist and librarian have ceased to work there, the roofs have been leaking, and the documentation is getting damp. The archive's documentation is at significant risk of being lost if it is not waterproofed and brought to a temperature suitable for its required preservation.

In 2020, the Inter-American Institute entered into an agreement with FLACSO Uruguay, whereby the latter assumed custody of the archive. In 2021, 2022, and 2023, the archive received aid from IberArchivos Spain, which enabled it to restore, classify, and relocate part of the collection to a room with suitable conditions for its preservation. As the only place in the world where they are preserved, the collection of the 'Pan American Child Congresses' was named Memory of the World by UNESCO in April 2024.

In the meantime, the rest of the collection continues to deteriorate, which highlights the urgent need to raise funds to refurbish the building and ensure it meets documentary conservation standards. To this end, we have an architectural refurbishment project in place to carry out repairs to the building.

Creation of Arab Studies Centre in FLACSO Uruguay

Interactions and relations between Arab and Latin American peoples. Lines of research in South–South cooperation.

The following lines of research seek to explore historical and contemporary connections between Arab regions and Latin America from a South–South perspective.

The term "Global South" (Meneses & Karina, 2018), formerly used interchangeably with "Third World" or "underdeveloped world", has historically been shaped by the concept of "coloniality of being" (Quijano, 2014). This notion posits that the identity and representation of Global South peoples have been defined by exogenous processes imposed by the Western world.

This coloniality has influenced the development and transmission of customs and traditions of native peoples throughout the Global South, and has also shaped an academic narrative that legitimised the dissociation between Latin America and "the Arab", in the sense described by Edward Said (1979) as "Orientalism".

With the advent of postcolonial, decolonial, and subaltern studies, a new narrative is being constructed from a southern perspective for southern audiences. In this context, studying the history of Uruguay alongside that of the Maghreb, Mashriq, and the Arabian Peninsula requires challenging the "cognitive injustice" (De Sousa Santos, 2022) inherited from Eurocentric and Western conceptions.

In order to achieve cognitive justice, it is essential to highlight the historical and cultural connections between Arab and Latin American peoples. In the nineteenth century, Latin American states witnessed a migratory and diasporic influx linked to the Ottoman Sultanate in the Maghreb and Levant. This influx continued in the early 20th century, coinciding with the open borders policy of José Batlle y Ordóñez.

Since 1948, migrants from Lebanon, Syria, and Palestine have arrived in the Río de la Plata region. It is estimated that 300,000 immigrants arrived in Latin America (Balloffet, 2024) and became part of the broader migratory wave that shaped the "melting pot of the society of the '900'".

During the 1960s, the Global South was engaged in anti-colonial struggles, leading to decolonization. In the Maghreb, Algeria and Egypt were central actors. Gamal Abdel Nasser advanced Arab unity and pan-Arabism. These processes had direct connections with Latin America, with Cuba and Algeria forging diplomatic ties and sharing ideological affinities.

The legacy of colonialism

The Global South, the Arab region, and Latin America share a colonial heritage. Both the Maghreb and Latin America experienced processes of independence that resulted in neo-colonial states. In the Maghreb, after the decline of the Ottoman Sultanate, European powers implemented the "Trusteeship System" to maintain control, while in the Caribbean the United States consolidated a neo-colonial system marked by economic dependence and political intervention, as seen in Cuba.

The anti-colonial struggles led to diplomatic relations and cooperation between Arab and Latin American countries. The OAS–League of Arab States summit in 1960 is one example of a forum aimed at strengthening economic and political collaboration.

The Palestinian conflict also contributed to new waves of diaspora, with countries such as Chile hosting important Palestinian communities and playing a role in regional debates on human rights and migration.

Identified lines of research

-

The construction of narratives based on identity and memory in Lebanese, Syrian,

and Palestinian refugee communities in Uruguay.

- This line of research examines how migrant communities in Uruguay maintain and transmit their identity, resistance, and sense of belonging. It focuses on narratives, collective memory, and the role of women in reconstructing their lives, as seen for example in the Palestinian community of Chuy.

-

An examination of the connections between liberation movements and anti-colonialism

in Latin America and the Maghreb.

- This line compares anti-colonial movements and their national projects, particularly the links between Algeria and Cuba in the 1960s, and the influence of Latin American struggles on artistic, literary, and cinematic production in Arab countries.

-

The representation of women as a symbol of the nation in Arab modernity, situated

between tradition and modernity.

- This line analyzes the symbolic and active role of women in the construction of national identity in the Maghreb and Mashriq, and compares Arab and Latin American modernities from interdisciplinary perspectives such as political science, history and sociology.

Research Proposal: Successful Educational Inclusion Experiences for Children with Autism

Project Title

Successful Educational Inclusion Experiences for Children and Youth with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) in Latin America and the Caribbean: Analysis of Pedagogical, Technological, and Collaborative Models

1. Introduction and justification

Inclusive education is a fundamental right and a global challenge, especially for students with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). The global prevalence of ASD is estimated at approximately 1 in 100 children. In Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC), support systems and neurodevelopment policies are often incipient and concentrated in major cities, leaving vast areas without coverage or specialized personnel.

The reviewed literature highlights that inclusive strategies such as the use of visual supports, augmentative and alternative communication systems, multisensory teaching, and educational robotics significantly improve integration and academic outcomes for students with ASD. However, research on the application and success of these strategies within the specific sociocultural and educational context of LAC is still scarce.

This project seeks to map and analyze successful inclusion practices in the region in order to provide an applicable framework of reference that can guide professional training, the design of public policies for child mental health, and the development of evidence-based inclusive pedagogical strategies.

2. Objectives

General Objective

To analyze and systematize educational inclusion experiences considered successful for children and youth with ASD in institutions across Latin America and the Caribbean, identifying pedagogical, technological, and collaborative elements that promote positive academic, social, and functional outcomes.

Specific Objectives

- To identify the pedagogical models and strategies that have proven most effective in improving communication, socialization, and basic academic skills.

- To determine the role and effectiveness of technological tools (ICT, educational robotics, alternative communication systems).

- To analyze support structures and interdisciplinary collaboration models involving teachers, therapists and families.

- To develop practical and contextualized recommendations for educational systems in the region.

3. Methodology

The study adopts a mixed-methods approach combining quantitative information at national level with in-depth case studies of successful experiences.

- Population: 8–10 successful educational experiences in countries of the region (Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Paraguay, Uruguay, Caribbean), approximately 100–150 participants.

- Qualitative techniques: semi-structured interviews, focus groups, participant observation, document analysis and life histories.

- Quantitative techniques: surveys using validated scales, outcome indicators and analysis of administrative data.

- Instruments: adapted interview guides, observation protocols, document analysis matrices, Likert-type questionnaires and specialized software.

- Analytical process: inductive–deductive coding, comparative case analysis, descriptive statistics and qualitative–quantitative triangulation.

- Ethical considerations: accessible informed consent, ethics approvals, anonymity and confidentiality, feedback of findings to participating institutions and equitable participation of children, families and educators.

4. Expected Results

- Systematization of successful educational inclusion experiences for children and youth with ASD.

- Intersectional analysis of how socioeconomic status, gender, ethnicity and geographic location affect access to and quality of inclusive education.

- Identification of key pedagogical, technological and collaborative factors that favour academic, social and functional development.

- Proposal of contextualized indicators to monitor inclusive education for students with ASD.

- Recommendations for public policies, teacher training programs and institutional improvement plans.

- Academic publications and participation in regional conferences on education, disability and mental health.

- Accessible dissemination products (guides, infographics, videos and policy briefs).

References

Detailed references include works by Alves (2022); Cangó & Benites (2025); Crane et al. (2024); Jiménez Granizo & Machado Sotomayor (2024); Machado & Machado (2025); Martillo Pachay & Carrión Macas (2025); Mendes de Almeida et al. (2025); Moya López et al. (2025); Pina & Santana (2025); and Vaquerizo et al. (2022).

About FLACSO System

The Latin American Faculty of Social Sciences (FLACSO), established in 1957, is an intergovernmental, multilateral and regional organization. Autonomous, academic and plural in nature, it comprises 18 Member States and 2 Observer Countries. Its mission is to promote the production of knowledge, teaching and research in the Social Sciences.

FLACSO conducts academic, research and technical cooperation activities across Latin America and the Caribbean, and actively participates in regional sociopolitical, cultural and economic debates.

The General Secretariat serves as FLACSO's legal and administrative representative, ensuring compliance with the institution's objectives and promoting the sustainability of the system.

Together with the Governing Board, it implements mandates of the General Assembly and the Superior Council, and coordinates regional initiatives aimed at development and integration of the system.

Dr. Rebecca Forattini Lemos Igreja, a distinguished Brazilian academic, assumed the position of General Secretary for the 2024–2028 term.

Education

FLACSO adapts to academic innovation, aligning its programs with current and future social needs. It offers a wide range of postgraduate programs, including master’s degrees, doctorates, specializations and diplomas.

Research

FLACSO conducts specialized academic research with both regional and global reach, producing analyses, diagnostics and publications that inform public debate.

Cooperation

A team of highly trained specialists develops technical and academic cooperation projects implemented through research, studies, workshops and training programs.

Internationalization

FLACSO plays a key role in the internationalization of Social Sciences in the region, promoting partnerships and agreements with multilateral, academic, governmental and civil society institutions.

Culture

Through FLACSO Cultural, the system promotes the rich cultural heritage of Latin America and the Caribbean via diverse cultural activities and initiatives.

- +20,000 individuals awarded postgraduate degrees.

- +100 postgraduate programs including doctorates, master’s and specializations.

- +1,800 academics, faculty and researchers.

- +300 annual research projects.

- +90 books published annually.

FLACSO addresses a wide range of topics in its research, teaching and cooperation activities, including:

- Geopolitics

- Democratic governance

- Access to justice

- Human rights

- Social inequalities

- Interculturality

- Gender and care

- Ethnicities and Afro-Latin identities

- Social and cultural diversities

- Discrimination and racism

- Migration

- Social and environmental sustainability

- Climate change

- Social and solidarity economy

- Sustainable community development

- Digital education

- Artificial intelligence

- Data protection and privacy

General Secretariat of FLACSO

- Email: secretariageneral@flacso.org

- Phone: +506 2253 0082

- Address: Av. 18A, Calle 75, El Prado, Curridabat, San José, Costa Rica

Academic Units in Latin America and the Caribbean

Headquarters:

- Argentina

- Brazil

- Chile

- Costa Rica

- Ecuador

- Guatemala

- Mexico

Programs:

- Cuba

- El Salvador

- Honduras

- Paraguay

- Dominican Republic

- Uruguay

Website and Social Media

- Website: www.flacso.org

- Facebook: flacsosg

- LinkedIn: flacsosg

- Twitter: @flacsosg